Can you imagine what it would be like to hallucinate the subjects of nightmares and disembodied voices, seek help from those around you, only to be rejected for fear of interacting with an individual persecuted by a god? Unfortunately, this has been the reality of many afflicted by schizophrenia in the past and even today.

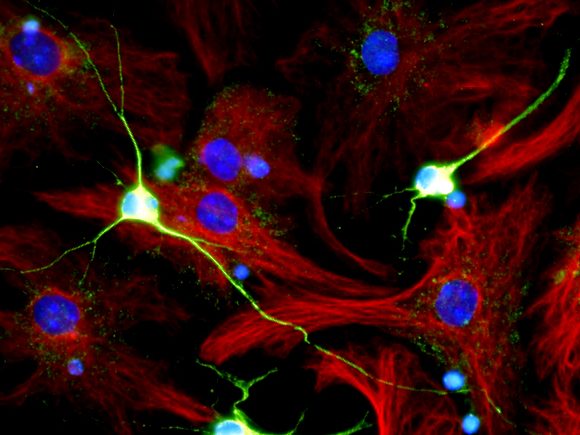

Schizophrenia is a chronic and often debilitating psychotic disorder that affects around 1% of people around the globe. Unfortunately, no one really knows what causes schizophrenia, but there are theories ranging from adverse childhood experiences, genetics, neurochemical imbalances, and/or the interaction of all these factors. While the cause of schizophrenia is unclear, it does include dysfunction of the prefrontal and temporal cortices. Specifically, these dysfunctions are mediated mainly through the imbalance of dopaminergic signaling, while serotonergic systems have also been implicated. As such, dopamine antagonists are used to treat schizophrenia as to reduce the effects of elevated dopamine levels in these brain regions. There are five different subtypes of schizophrenia – paranoid, disorganized, catatonic, and residual schizophrenia; and schizoaffective disorder – all characterized by different collections of positive and/or negative symptoms. Positive symptoms referring to the gain of some function/experience – delusions, feelings of persecution and grandiosity, and hallucinations – and negative symptoms referring to the loss of some function/experience – flat affect, cognitive impairments, loss of motivation, and psychomotor disturbances.

Schizophrenia, even though it has slightly improved over the past decade, has always had extremely negative connotations. Dating back to the Roman Empire, it was believed that schizophrenia, and the “madness” that results, was a punishment from the heavens. Or, going slightly later, demonic possession. Astonishingly enough, there was an author in 1563, Johann Weyer, who went against the idea of schizophrenia being a punishment from the gods or demonic possession, stating that it was simply a result of natural causes. However, the Church banned this book and accused its author of sorcery. Suffice to say, the early years of schizophrenia were punctuated by a fear of its symptoms. Individuals suffering from schizophrenia were often placed into psychiatric institutions for fear of their behavior, burned at the stake for being a receptacle for the devil, ostracized and avoided for fear that they would force others to fall victim to their unpredictable behaviors, etc. To give the institutions and people of the past some credit, the characteristic symptoms of schizophrenia – including paranoid delusions and auditory hallucinations – would be fear-inducing in the people of old, especially when they had no concept of mental illness. Thus, their perceptions were informed by their religious beliefs and fears, leading them to establish a negative stigma with schizophrenia, something that would persevere for centuries. To avoid a completely western lens, it is worth noting that there are people with schizophrenia, although undiagnosed, who are seen as being possessed or divinely gifted in some cultures.

Delving further into the history of schizophrenia, the term “schizophrenia” is relatively new, being coined by Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1911. In addition to coining the term, he also was the first to describe its symptomology as positive and negative. Before being labeled “schizophrenia”, it was referred to as dementia praecox due to it being believed to be a form of dementia. While this classification is not entirely incorrect, it is not necessarily accurate. While schizophrenia patients due have a higher risk of developing dementia, due to the excitotoxicity-induced neurodegeneration in the prefrontal and temporal cortices – both of which being related to forms of dementia – it is not guaranteed that all individuals with schizophrenia will also be diagnosed with dementia later in life. A marked shift in the classification of schizophrenia was the acknowledgement of negative symptoms alongside the positive symptoms. In 1904, psychiatrist Erwin Stransky was the first to emphasize the affective dimension of schizophrenia. Something that would be reinforced by psychiatrist in later years, including Bleuler. Following Bleuler’s classification of this disorder as “schizophrenia”, there was a marked shift in how schizophrenia was perceived: the dichotomous perspective. This new perspective split the symptoms of schizophrenia into fundamental and accessory, and primary and secondary symptoms. The first category of this dichotomy – fundamental and accessory symptoms – was entirely descriptive. Fundamental symptoms were those that were chronically present and included alterations in thought, affectivity, and attitude towards the world. Accessory symptoms were those that were transient in nature –hallucinations and delusions. The second category, primary and secondary symptoms, was a more theoretical approach focused on symptoms caused by the pathological process of schizophrenia and the symptoms that precipitate from the “reaction of the sick psyche”. While this is not the only approach to the classification of schizophrenia symptomology, it was arguably the most influential in cementing its place in the psychiatric sphere. Following this cementation, pharmacological methods have been developed to treat this disorder, namely antipsychotics, so that patients with schizophrenia are not wholly debilitated and can live a relatively “normal” life.

To wrap it up, as ludicrous as it may be to claim this, schizophrenia is most likely not a result of demonic possession or punishment from a supernatural being, but of a neurodevelopmental abnormality. In addition, it is marked by dysfunctions in dopaminergic signaling in the prefrontal and temporal cortices, and whose symptomology typically precipitates following an extremely stressful life event between the ages of 16-25. Like many others, it is a mental disorder has a past marked by misunderstanding that has only added to the suffering of those afflicted with it. This misunderstanding often leading to the isolation of these individuals, maltreatment by virtue of them being seen as “crazy” or less “aware” than a normal person, etc. On the bright side, this misunderstanding has been slowly but surely dismantled over the last century. So, the next time you might interact with someone who might be afflicted with schizophrenia, try to see them as a human being afflicted with a mental disorder rather than the mental disorder personified.

Dollfus, Sonia, and John Lyne. “Negative Symptoms: History of the Concept and Their Position in Diagnosis of Schizophrenia.” Schizophrenia Research, vol. 186, 2017, pp. 3–7., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.06.024.

Egan, Michael F, and Daniel R Weinberger. “Neurobiology of Schizophrenia.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology, vol. 7, no. 5, 1997, pp. 701–707., https://doi.org/10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80092-x.

“Frequently Asked Questions about Schizophrenia.” Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, 23 Aug. 2019, https://www.bbrfoundation.org/faq/frequently-asked-questions-about-schizophrenia?gclid=Cj0KCQjwk7ugBhDIARIsAGuvgPb7uOrHkgn3ubnmQgapklbrHonROhrT1MmIzZauDW7kG-rapGI_SHAaAkm6EALw_wcB.

“Treatment – Schizophrenia.” NHS Choices, NHS, https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/schizophrenia/treatment/.