It is typical to find children engaging in some act of play: playing dress-up, playing pretend, or playing tag with others. During development, children must partake in play. It allows them to learn about the world around them creatively while developing the social, emotional, and cognitive skills necessary to navigate life. For adults, playfulness is also necessary to reduce stress and improve mood. We all enjoy having a bit of fun, regardless of age. Overall, play is critical for a healthy and balanced life. Play is the least understood of all classes of mammalian behaviors compared to other behaviors such as “sexual, aggressive, and fear behavior” on a neurobiological level (Gloveli et al., 2023). However, due to lesion studies, it is known that play can proceed without cortical activity. We also know that brain circuitry associated with reward is essential in maintaining playful behaviors, such as being ticklish. In a study conducted by Gloveli et al., the role of periaqueductal gray (PAG) in play is investigated (2023). The PAG is a small midbrain region surrounding the cerebral aqueduct, which holds the brain’s buoyant force, cerebrospinal fluid. The PAG is involved in various functions, including pain modulation, heart rate and blood pressure regulation, autonomic processes such as bladder control, and mammalian vocalizations (Behbehani, 1995).

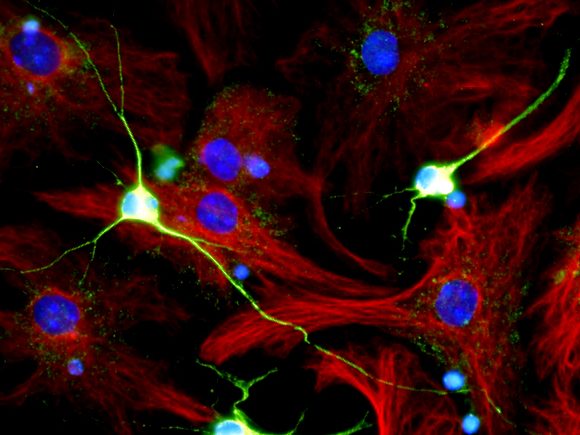

Rats are playful creatures. Much like humans laugh in response to being tickled, rats use vocalizations at a pitch of 50 kHz to indicate playful behavior and positive affect. Alongside this vocal measure, they also tested the rodents in anxiety-inducing conditions, where play behavior is known to be suppressed. To locate neural correlates of playful behavior, neural recording devices known as Neuropixels and Tetrodes were used. The research team aimed to answer research questions such as “Is the PAG required for play?” and “Do neurons in the PAG respond to touching, tickling, and play?” (Gloveli et al., 2023).

While multiple experiments were performed in this study to assess the PAG’s role in playful behavior, one experiment is particularly interesting as it uses the rat’s behavioral and neural responses to being tickled to measure playfulness. Blocking experiments using injections of muscimol or lidocaine were performed to investigate the PAG’s association with ticklishness and playfulness. Previous studies have found that the more ticklish the rat is, the more playful it will be (Panksepp, 2003). Injection of muscimol, a GABA receptor agonist, blocked the PAG. GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, which means that it can reduce or suppress the activity of neurons. Gloveli et al. found that blocking the activation of neurons in the PAG led to decreased overall playful behavior (2023). Playful behavior was initiated through a rat-human paradigm, where the human experimenter tickles the rat on its back for 5 seconds and its stomach for 5 seconds and then encourages the rat to chase the experimenter’s hand to study play-evoked responses. Results from this experiment show that overall engagement in playful behavior decreased following inhibition of the PAG: the desire to play decreased, and vocal responses of 50 kHz were significantly reduced. Responses to gentle touch were also compared to tickling responses, and as hypothesized, vocal responses increased from gentle touch on the back to tickling on the back to tickling on the rat’s stomach. Overall, the results of this study favor the correlation between the PAG and playfulness and even identify cells specific to play excitement in the lateral columns of the PAG.

While the identification of the periaqueductal grey as a region essential for playfulness is supported by this preliminary study, the PAG does not work alone. Brain activity is highly complex, and a response to a single stimulus often involves the coordinated activity of multiple regions across the brain. Brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex, lateral hypothalamus, somatosensory cortex, and amygdala initiate and modulate controlled emotional responses to stimuli. Given that play is a multifaceted behavior involving cognitive, emotional, and social elements, future research may delve into the interplay between these dimensions and the neural mechanisms identified in the PAG to expand our understanding of the holistic nature of play. The findings on the role of the periaqueductal gray (PAG) in playfulness in rats lay the groundwork for potential application in understanding play behavior across various mammalian species, including humans. Although it is not yet well understood what other neural circuitry is involved and at what level it is coordinated with activity in the PAG, we do know one thing for sure: rats are ticklish, too!

Sources:

Behbehani, M. (1995). Functional characteristics of the midbrain periaqueductal gray. Progress in

Neurobiology, 46(6), 575-605.

Gloveli, N., Simonnet, J., Tang, W., Concha-Miranda, M., Maier, E., Dvorzhak, A., . . . Brecht, M. (2023). Play

and tickling responses map to the lateral columns of the rat periaqueductal gray. Neuron (Cambridge,

Mass.), 111(19), 3041-3052.e7.

Panksepp, J. (2003). At the interface of the affective, behavioral, and cognitive neurosciences: Decoding the emotional feelings of the brain. Brain and Cognition, 52(1), 4-14.

This is a very detailed discussion of a very important (and little researched) topic! Thank you!

LikeLike