Every night, like clockwork, our eyelids get heavy, thoughts start to blur, and we drift off, only to wake up hours later to a new day with new energy. Now, imagine if that relief does not come. About 50-70 million Americans suffer from sleep disorders. The most common of these disorders is insomnia. Insomnia is defined as chronic dissatisfaction with sleep quality or quantity that is characterized by difficulty falling or returning to sleep, frequent nighttime awakening, and/or waking earlier in the morning than desired (Levenson).

In a study exploring the experiences of those experiencing chronic insomnia, the extent to which the effects of this disease can decrease a person’s quality of life is shown. One participant explained “All things in my life have been changed; I start the morning with fatigue and low energy. I cannot do my work such as shopping, cooking, and playing with my daughter. It is hard to stand” (Rezaie). While another participant stated “Insomnia is too bad, even worse than cancer. It’s like a loss, or worse than a loss. My son died last year. I was very sad, but I could sleep. Now, I think, it is more tolerable than insomnia”(Rezaie). Lack of sleep resulting from insomnia can cause impaired cognition, weight gain, worsened memory, and higher levels of anxiety, along with long-term problems such as a higher risk for stroke, depression, diabetes, heart disease, and breast cancer (Mayo Clinic). Often described as the “silent death,” insomnia can be detrimental to mental and physical health. Its effects should not be underestimated.

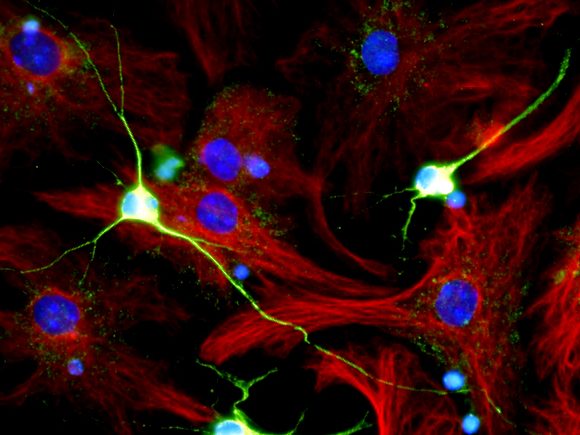

So, how do we reach this state of rest that is so vital for our minds and bodies? The answer lies in brain networks. In order to initiate and maintain sleep, the arousal regions of the brain need to be inhibited. This inhibitory process is accomplished by neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) of the anterior hypothalamus with the addition of a synergistic effect provided by orexin neurons in the lateral hypothalamus (Carley). Regions of the brain that the VLPO inhibits include the tuberomammillary nucleus, lateral hypothalamus, locus coeruleus, dorsal raphe, laterodorsal tegmental nucleus, and pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus. Although the molecular triggers that activate the VLPO and initiate sleep onset have not yet been wholly defined, there is substantial evidence that points to extracellular adenosine to be a candidate. Adenosine accumulates in the basal forebrain during wakefulness and then diminishes with ongoing sleep. Adenosine receptors are expressed in the VLPO, and adenosine activates VLPO neurons in vivo; thus, it is possible, that adenosine acts as a “sleep switch” for our bodies (Brinkman).

Exploring more scientific terms, insomnia is described as a disorder of hyperarousal corresponding with increased somatic, cognitive, and cortical activation. While there is no universal blueprint for the mechanism behind insomnia, there have been a number of causes and risk factors that have been identified. One of these causes is the dysfunction of brain networks, such as the one discussed above. This has been observed through animal models, as it was discovered that lesions in the dorsomedial thalamus, anterior ventral, raphe nucleus, or the VLPO result in insomnia (Levenson). While this is one example, it is important to remember insomnia is a multifaceted disease, and there are many other causes.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the current first-line treatment for insomnia. These therapies, which may involve stimulus control therapy, relaxation methods, sleep restriction, remaining passively awake, and light therapy, aim to teach healthy sleep habits and behaviors. CBT is typically as effective as or even more effective than sleep drugs. However, for those who find CBT ineffective, some short-term and a limited number of long-term prescription drugs are available. Prescription drugs often have adverse side effects during wakefulness, such as grogginess, a higher risk of falling, etc. Symptoms are particularly prevalent with long-term medication regimens, since there is no universal best method of administration, leaving the risk, and reward to be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Sleep is vital to everyday function. Yet many still struggle with it, which opens the door for more research and discussion. A better understanding of the disease mechanism is the key to producing the best, most precise, therapeutic results.

References:

“Brain Basics: Understanding Sleep.” National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, http://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/public-education/brain-basics/brain-basics-understanding-sleep. Accessed 10 Apr. 2024.

Carley, David W., and Sarah S. Farabi. “Physiology of sleep.” Diabetes Spectrum, vol. 29, no. 1, 1 Feb. 2016, pp. 5–9, https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.29.1.5.

“Insomnia.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 16 Jan. 2024, http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/insomnia/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20355173.

Levenson, Jessica C., et al. “The pathophysiology of insomnia.” Chest, vol. 147, no. 4, Apr. 2015, pp. 1179–1192, https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-1617.

Rezaie, Leeba, et al. “Exploration of the experience of living with chronic insomnia: A qualitative study.” Sleep Science, vol. 9, no. 3, July 2016, pp. 179–185, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.slsci.2016.07.001.