Picture this: the deafening honks, the screeching tires, and the pulsating anger simmering just beneath the surface. Welcome to the perilous world of road rage, where tempers flare and civility takes a back seat to chaos. The hypothalamus, a crucial region of the brain located below the thalamus, plays a significant role in regulating various physiological and behavioral functions, including aggression and rage. It serves as a vital center for integrating signals from the nervous system and hormonal systems to coordinate responses to environmental and internal stimuli. The hypothalamus converts nervous system input into endocrine signals and releases high levels of releasing hormones, somatostatin, and dopamine to the anterior pituitary gland. When it comes to aggressive behavior, the hypothalamus is implicated in both the initiation and regulation of these responses.

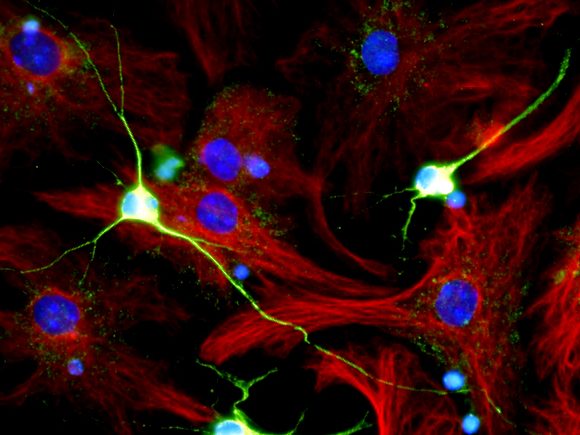

One of the key areas within the hypothalamus associated with aggression and rage is the ventrolateral part of the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH). This is a small subnucleus in the medial part of the hypothalamus. Studies in animals, such as rodents, have demonstrated that lesions or stimulation of the VMH can lead to profound changes in aggressive behavior (Hashikawa et. al, 2017). Stimulation of this region can trigger intense displays of aggression, while lesions can result in reduced or absent aggressive responses. Researchers implanted electrode microwires to the VMH in mice during stereotactic surgery. They then stimulated the mice with a variety of social and nonsocial stimuli, including intact and anesthetized male mice, female mice, castrated male mice, food, mouse urine, and novel objects such as a plastic test tube (Falkner et. al, 2014). The resulting behavior was classified as social behavior, nonsocial behavior, or attacks. Researchers saw the most VMH neurons active during male-male interactions, which correlates to when they saw the most attack-like behavior from each subject (Falkner et. al, 2014). A similar experiment found that conspecific males (i.e., male mice of the same species) have higher firing neurons in VMH related to territorial aggression and did not attack mice of a distinct species when housed together (Yang et. al, 2017). This suggests that the VMH plays a crucial role in initiating and promoting aggressive behaviors within the same species.

Moreover, the hypothalamus is involved in the modulation of the autonomic nervous system, which controls physiological responses associated with aggression. This includes changes in heart rate, blood pressure, and hormone release, all of which may accompany aggressive or rageful states (Bandler et. al, 2000). The release of certain neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and serotonin from the hypothalamus to other brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and the brain stem further modulates aggression (Falkner et. al, 2014). These neurotransmitters can influence the threshold for aggressive responses and the intensity of the behavior. Zhang et. al conducted an experiment that measured the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A serotonin receptors in male and female rats. The only sex-related difference in the expression of 5-HT2A receptor was seen in the VMH, with male rats having a drastically higher expression than females (Zhang et. al, 1999). This study also focused on the difference between gonadectomized (mice with their testis removed) and control male rats and found higher 5-HT1A activity in rats who had their reproductive organs removed. They concluded that there is a connection between gonadectomy, testosterone and serotonin levels (Zhang et. al, 1999). This interplay shows mood, behavior, and cognitive processes all relate to aggression.

In conclusion, the hypothalamus emerges as a central hub for the orchestration of aggressive and rageful behaviors. Through its connections with various brain regions and modulation of autonomic responses, the hypothalamus plays a pivotal role in both the initiation and regulation of aggression. Further research into the intricate neural circuits and molecular mechanisms within the hypothalamus promises to deepen our understanding of these complex behaviors and potentially offer insights into managing aggressive tendencies in various contexts. Understanding the hypothalamus’ role in processing anger could pave the way for effective interventions aimed at reducing road rage.

Works Cited:

Bandler, R., Keay, K. A., Floyd, N., Price, J., Bandler, & C.E. (2000) Central circuits mediating patterned autonomic activity during active vs. passive emotional coping. Brain Research Bulletin, 53(1), 95-104, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0361923000003130?via%3Dihub

Falkner, A. L., Dollar, P., Perona, P., Anderson, D. J., & Lin, D. (2014, April 23). Decoding Ventromedial Hypothalamic Neural Activity During Male Mouse Aggression. Journal of Neuroscience. https://www.jneurosci.org/content/34/17/5971?etoc=&csrt=2637806494682357185

Hashikawa, Y., Hashikawa, K., Falkner, A. L., & Lin, D. (2017, November 28). Ventromedial hypothalamus and the generation of aggression. Frontiers In Systems Neuroscience. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnsys.2017.00094/full

Yang, T., Yang, C. F., Chizari, M. D., Maheswaranathan, N., Burke, K. J., Borius, M., … & Shah, N. M. (2017). Social control of hypothalamus-mediated male aggression. Neuron. 95(4), 955-970. https://www.cell.com/neuron/pdf/S0896-6273(17)30598-6.pdf

Zhang, L., Ma W., Barker L.J., Rubinow, D.R. (1999). Sex differences in expression of serotonin receptors (subtypes 1A and 2A) in rat brain: a possible role of testosterone. Neuroscience, 94(1), 251-259, ISSN 0306-4522, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306452299002341?casa_token=vqfFwaXOXGwAAAAA:v-u-5R6-ktLJNo-5k-hsgCfYu6rx07c4BhcJ93oUVxkWZxdeBumoX_zM-Wfw-ZpLxbaGzIpWaA