Undergoing limb amputations due to traumatic injuries from accidents and violence can be a devastating experience. Becoming even more prevalent is the rise in diabetes cases that can lead to amputation through peripheral arterial disease or because of diabetic neuropathy. Limb amputation can have debilitating physical and psychological effects for its victims, however, most people are unaware of the effect that limb loss can have on the brain.

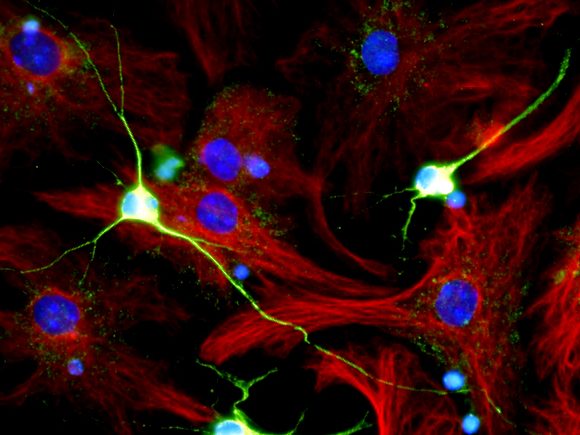

The brain’s sensory and motor cortices are topologically organized in a way that spatially represents where the different body parts are controlled on the brain’s surface. This “somatotopic” arrangement was explained by Penfield and colleagues in the mid 20th century, from experiments in which they discovered that stimulating the corresponding region in an animal’s primary motor cortex elicited consistent movements. Further research showed that this organization, while in a slightly different manner, was also present in the primary somatosensory cortex. For example, the incoming sensory information from one’s hand can be predictably located to the surface of the parietal lobe. This recognized configuration provides a baseline from which sensory and motor integration occurs in the central nervous system. More recently it has been hypothesized that for these areas of the brain to remain functional and organized, consistent utilization of the brain areas through receiving touch sensation are necessary. In fact, on the cellular level, for neurons to maintain their connectivity, the must be sending signals between them. This seems to pose an interesting problem to those who unfortunately undergo amputation of a limb since their sensory connections through that limb have been severed.

Research on both humans and primates with amputated limbs has shown how the brain deals with a lack of sensory input. Interestingly, the brain has some ability to reorganize the area of lost input to incorporate adjacent areas of the “homunculus”, or body organization of the brain. A variety of brain imaging techniques including fMRI and PET scans illustrate how the typical brain region that corresponds to the hand gets invaded by activity from other nearby body representations, like the face, long periods of time after amputation. These findings convey the plasticity of the brain to repurpose unused connections. A recently discovered caveat of these findings, however, is that despite some blurring of boundaries and encroachment of other regions, the neural organization associated with the missing hand is not completely abolished even a decade after injury. The territory and its synaptic connections are somewhat preserved over time. This finding provides promising insights into how future neuroprosthetics could be developed to help amputees control artificial limbs with their own remaining neural pathways.

Recently, biomarkers of neuronal health were measured in the brains of amputees and those who have had limbs reattached or transplanted. Levels of N-acetylaspartate (NAA), a chemical associated with neuronal health, were found via magnetic resonance spectroscopy to be decreased in the brain region associated with missing limbs. Even when patients were able to receive a limb transplant or have their own limb successfully reattached after injury, neuronal health was markedly decreased. The peripheral nerves in limbs have an amazing capacity to repair themselves, making reattachment surgeries like this possible. These new findings, however, show that even after successful reattachment, nerve damage can have permanent effects on the mature brain which has limited ability to repair itself. Research on the somatotopic organization of brain regions after amputation has immense room to expand in order to help us understand and potentially alleviate the damage caused by these injuries. Will we be able to utilize remaining connectivity to engineer next-generation prosthetics, or does severing sensory inputs all but guarantee irreparable brain damage and neural rigidity?

Sources

Cirstea CM, Choi IY, Lee P, Peng H, Kaufman CL, Frey SH. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of current hand amputees reveals evidence for neuronal-level changes in former sensorimotor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2017 Apr 1;117(4):1821-1830. doi: 10.1152/jn.00329.2016. Epub 2017 Feb 8. PMID: 28179478; PMCID: PMC5390283.

Kikkert S, Kolasinski J, Jbabdi S, Tracey I, Beckmann CF, Johansen-Berg H, Makin TR. Revealing the neural fingerprints of a missing hand. Elife. 2016 Aug 23;5:e15292. doi: 10.7554/eLife.15292. PMID: 27552053; PMCID: PMC5040556.

Makin TR, Flor H. Brain (re)organisation following amputation: Implications for phantom limb pain. Neuroimage. 2020 Sep;218:116943. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116943. Epub 2020 May 16. PMID: 32428706; PMCID: PMC7422832.