Have you been keeping up that Duolingo streak? Let’s conduct a little experiment. Read the following sentence: “Hola, my name es Jane Doe y I am an estudiante studyiando Biology.” This sentence was crafted to follow the syntactical and semantic rules of both English and Spanish, with words that are either cognates (es), high-frequency words in English (I) or Spanish (y), or a word that technically does not follow the orthography of either language alone, but rather both at the same time (studyiando).

It should come as no surprise that the more fluent one is in both languages, the easier it is to comprehend this amalgamation of a sentence. This phenomenon draws from the concept of code-switching, which is the process of “shifting from one linguistic code to another” and that research shows, “for early fluent bilinguals, code-switches are not processed as semantic violations and the brain can prioritize the meaning of words regardless of which language they appear in during sentence reading” (Blackburn, et. al). How can this be the case?

Bilinguals process language by first receiving the visual stimulus of the words and accessing the meaning of the words in all languages understood by the brain, an idea that the BIA+ model of word recognition seeks to reproduce. In the BIA+ model, semantic retrieval occurs simultaneously, meaning that one can retrieve a definition before even recognizing the language. This model then requires that one word from one language be inhibited so that the correct one is understood and spoken. Therefore, the neural differences between monolinguals and bilinguals are due to the extra task of controlling when each language is used, and the energy required to switch to one language’s body of words and syntax over the others.

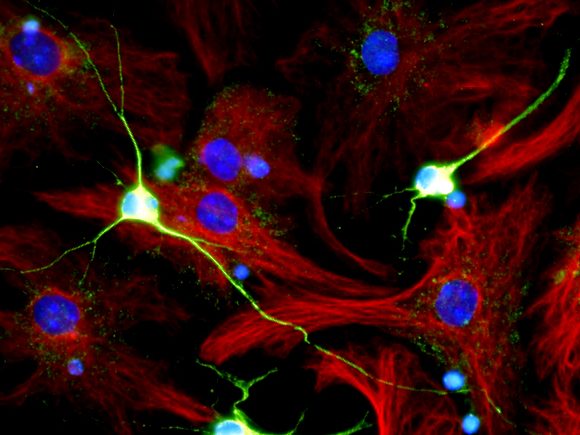

The BIA+ model runs opposite to a less supported psycholinguistic model, the serial language recognition system, that says words are first filtered through language membership recognition (deciding what language the word is in) before accessing any meaning. Both models illustrate language processing, and explain why bilinguals show increased activity in multiple areas of the brain, like the left caudate head that helps in language control, when undertaking different linguistic tasks in only one language (their native). Because of this heightened activity, the brain shows increases in gray matter in areas such as the left inferior parietal structures, left putamen, and Heschl Gyrus, which together aid in producing fluent speech and processing auditory information. White matter tracts have also shown increased integrity in the corpus callosum for bilinguals, even those who learned the second language much later in life.

What then are the implications for these neural differences? Studies suggest bilinguals present signs of cognitive decline four to five years after their monolingual counterparts. This is thought to be due to their increased white matter integrity and increased gray matter, allowing for secondary routes of information around potentially decaying areas. In addition, bilinguals in all age groups tend to perform better in attentional tasks, potentially due to increased activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, which controls executive attention.

Hear me out: don’t keep letting those Duolingo notifications stack up without paying them any mind. Consider the benefits of learning a second language and keep at it. What seems like mental gymnastics now, can become “second nature” with time and practice.

References

Bialystok, Ellen et al. “Bilingualism: consequences for mind and brain.” Trends in cognitive sciences vol. 16,4 (2012): 240-50. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2012.03.001

Blackburn, Angélique M, and Nicole Y Y Wicha. “The Effect of Code-Switching Experience on the Neural Response Elicited to a Sentential Code Switch.” Languages (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 7,3 (2022): 178. doi:10.3390/languages7030178

Costa, Albert, and Núria Sebastián-Gallés. “How does the bilingual experience sculpt the brain?.” Nature reviews. Neuroscience vol. 15,5 (2014): 336-45. doi:10.1038/nrn3709

Morrison, Carlos D.. “code-switching”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 30 Sep. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/code-switching. Accessed 18 October 2024.