Every time you take a walk, eat a meal, or even blink, these actions are made possible by the proper functioning of your myelin sheath. Every thought, movement, and reflex, depends on the smooth, rapid transmission of signals called action potentials propagating through the axons of the central nervous system. The myelin sheath that surrounds these axons enables that speed and precision, making it essential to nearly everything we do. This means that disorders that affect the myelin sheath, like Alexander Disease, can have especially devastating effects on the normal functioning of neurons.

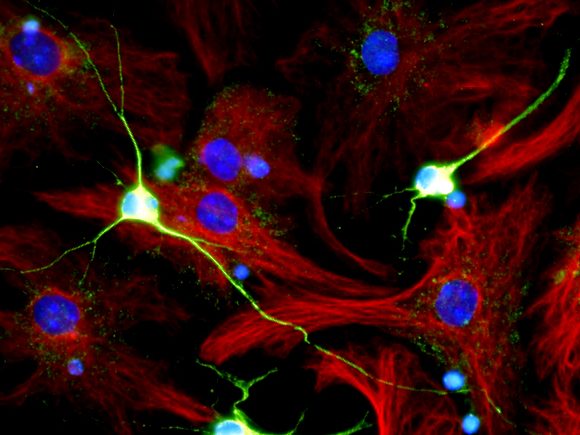

Alexander Disease is a rare, usually fatal neurodegenerative disease which belongs in the class of leukodystrophy disorders. Leukodystrophy disorders are a group of relatively rare, progressive, genetic disorders which affect the white matter of the central nervous system. The brain is made up of both gray matter and white matter. The white matter in the brain is predominantly made up of myelinated axons, and leukodystrophy disorders are characterized by the abnormal development or degeneration of the myelin sheath. Alexander disease is caused by a mutation on chromosome 17 in the GFAP gene. This mutation can be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, meaning that only copy of the mutated gene would need to be passed down for an individual to have this condition. However, it most often arises spontaneously without any genetic history. The GFAP gene codes for the glial fibrillar acidic protein, which makes up a large component of intermediate filaments in astrocytes, a type of glia. This makes Alexander Disease the only known disorder that causes a genetic abnormality that affects astrocyte cells. Normally functioning astrocytes play an important role in supporting and providing nutrients to the myelin sheath. The mutation in the GFAP gene has the opposite effect, however. Instead of supporting the myelin sheath, accumulation of GFAP forms groups called Rosenthal fibers. Rosenthal fibers are aggregations of protein found in the cytoplasm of glial cells. These protein clumps break down the myelin sheath and cause the death of surrounding glial and neuronal cells.

Symptoms of Alexander Disease most often first arise in infants and children, and the disease is typically more severe the earlier in life symptoms appear. The most common presentations of the disease include seizures, enlarged brain and head, and physical and intellectual developmental delays. This disorder was traditionally broken down into four categories based on symptom picture and the age when symptoms first appeared. However, the classification of Alexander Disease was revised in 2011, and it is now broken down into Type I and Type II classifications. Type I is more severe, often develops before the age of four, and has an average survival age of 14 years. It is largely characterized by seizures, accumulation of cerebral spinal fluid in the brain, motor delay, and encephalopathy. Type II Alexander Disease is less severe, and symptoms first present after the age of four. It is marked by impaired muscle control and coordination, difficulty swallowing, and speech problems. Due to the variability of symptoms, a diagnosis of Alexander Disease requires an MRI or CT scan to visualize the structures of the brain and test for a genetic predisposition.

Unfortunately, there is currently no cure or way to stop the progression of Alexander Disease. Current treatment options center around palliative care and symptom management, and treatment varies depending on the symptoms that an individual presents with. Some treatment options for those with Alexander Disease include anti-seizure drugs, a ventriculoperitoneal shunt to remove excess cerebrospinal fluid in the brain, physical therapy, and the use of specialized equipment to aid in mobility and improve muscle stiffness. Current scientific research on Alexander Disease is focused on exploring how decreasing the expression of the GFAP gene could serve as a potential future avenue for treatment.

Works cited

Kuhn, James, and Marco Cascella. “Alexander Disease.” PubMed, StatPearls Publishing, 2020, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562242/.