The last place I expected to see a neuroscience presentation was in the middle of an art exhibit, but the Scottsdale Museum of Modern Art proved me wrong. As my mother and I walked through the halls, mirrored illusions and intricate paintings shared the walls with TVs explaining the neural pathways involved in evoking emotions from brushstrokes on a canvas. At the center of it all? A small section of the brain that basically only humans have, also known as the fusiform gyrus.

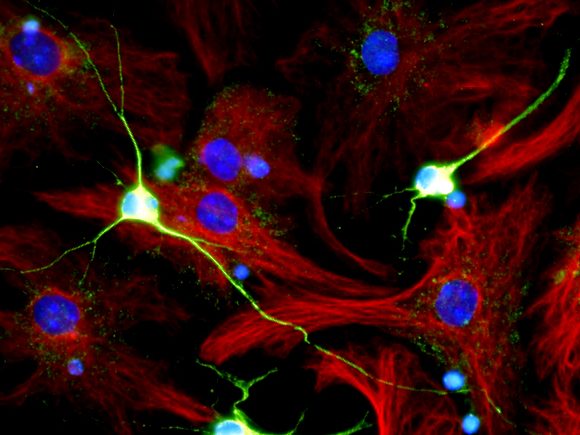

The fusiform gyrus is a ridge located on the ventral (bottom) surface of the brain’s cortex. Situated at the border between the temporal and occipital lobes, it resides next to the brain’s main visual centers. The fusiform gyrus is involved in many complex behaviors and processes almost exclusive to humans. Most of its functions deal with visual processing, receiving a lot of information from its neighbor, the primary visual cortex. However, the right and the left fusiform gyrus each have different specialties. The left fusiform gyrus contains a section called the visual word form area. This area is highly active in language processing, reading, and spelling. The right fusiform gyrus is a little more involved in three dimensions. Identifying faces and distinguishing individual parts of complex objects is the job of the fusiform face area (FFA) in the right fusiform gyrus.

Have you ever looked up at night and seen the man in the moon? If you have, you can thank the fusiform face area! The fusiform face area is incredibly reactive to faces, both in real life and on a page. Studies on individual neurons show that FFA neurons respond to faces at much higher frequencies than neurons from other parts of the brain. The fusiform face area is so well primed to recognize elements that make up a face (eyes, nose, mouth) that it can activate for “face-like features” in images or objects that don’t have a face. This phenomenon is called pareidolia. This ability also helps people recognize non-real faces in different forms of art, from realistic to heavily stylized. The Mona Lisa and an emoticon both smile, after all :-).

An ill-functioning fusiform gyrus can result in difficulties recognizing many different symbols and objects. For example, damaging the visual word form area can cause alexia, or the inability to read written languages. This also applies to codes, like sheet music. Damaging the fusiform face area can lead to a condition called prosopagnosia. Also called face blindness, this is where a person is unable to distinguish between faces, even of people they’ve known all their life. A similar lack of facial and emotional recognition has been associated with lowered activity in the fusiform face area in imaging studies of autistic individuals, further implicating the fusiform gyrus in differentiating facial cues. Interestingly, autistic brains also showed an unusual density of gray matter in their right fusiform gyri, showing that there are still many mysteries the fusiform gyrus holds.

The fusiform gyrus’ ability to connect individualized parts of a visual stimulus and place them into an identifiable whole is an incredible feat. Not only is it a trait that sets us apart as people, it influences aspects of every single day. Between spotting a friend across the street and reading a delayed bus schedule, we don’t even realize we’re using it! While most identified in human specialized facial recognition, the ability to distinguish the individual elements of what one is looking at and find the whole picture, so to speak, is a type of pattern recognition that we use every single day in just about every type of situation. Whether finding the face in an abstract painting or picking out the letters in a horribly pixelated PDF, the fusiform gyrus helps keep the world recognizable.

Works Cited

Akdeniz, G., Toker, S., & Atli, I. (2018). Neural mechanisms underlying visual pareidolia processing: An fMRI study. Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 34(6), 1560–1566. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.346.16140

Baarns, B. J., & Gage, N. M. (2013). Fundamentals of Cognitive Neuroscience. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/c2011-0-04186-8

Floris, D. L., Llera, A., Zabihi, M., Moessnang, C., Emily, Mason, L., Rianne Haartsen, Holz, N. E., Mei, T., Elleaume, C., Vieira, B. H., Pretzsch, C. M., Forde, N. J., Baumeister, S., Flavio Dell’Acqua, Durston, S., Banaschewski, T., Ecker, C., Holt, R. J., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2025). A multimodal neural signature of face processing in autism within the fusiform gyrus. Nature Mental Health, 3(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00349-4

Moreno, R. A., & Holodny, A. I. (2021). Functional Brain Anatomy. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America, 31(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nic.2020.09.008

Palejwala, A. H., O’Connor, K. P., Milton, C. K., Anderson, C., Pelargos, P., Briggs, R. G., Conner, A. K., O’Donoghue, D. L., Glenn, C. A., & Sughrue, M. E. (2020). Anatomy and white matter connections of the fusiform gyrus. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 13489. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70410-6

Sy, S. (2024, November 27). “Brains and Beauty” exhibit explores how the mind processes art and aesthetic experiences. PBS News. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/brains-and-beauty-exhibit-explores-how-the-mind-processes-art-and-aesthetic-experiences

Wardle, S.G., Taubert, J., Teichmann, L. et al. Rapid and dynamic processing of face pareidolia in the human brain. Nat Commun 11, 4518 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18325-8

Weiner, K. S., & Zilles, K. (2016). The anatomical and functional specialization of the fusiform gyrus. Neuropsychologia, 83, 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.06.033

Zhang, W., Wang, J., Fan, L., Zhang, Y., Fox, P. T., Eickhoff, S. B., Yu, C., & Jiang, T. (2016). Functional organization of the fusiform gyrus revealed with connectivity profiles. Human brain mapping, 37(8), 3003–3016. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23222